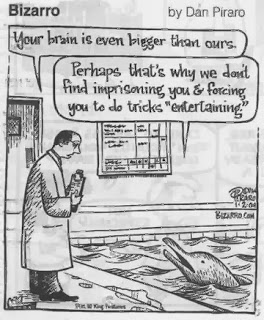

Should we enjoy the tricks a slave performs for her masters?

Can an animal be a slave? What follows is a conversation among members of The Society for Descriptive Psychology about the status of captive animals who are possible persons.

Should we only recognize others who share our human embodiment as a fellow person? What we accredit as a person matters legally, morally, and ethically. People are offered rights, privileges, and protections not given to non persons. As a community, we no longer allow one person to be the property of another person. When we own people and require them to act as we wish, they are slaves.

Slavery is enforced by coercion. Coercion elicits resistance and resigned compliance.

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 13, 2013 7:25:52 AM MST

What we count as a person matters. Are humans the only persons?

A conference at Yale in December:

Do you enjoy SeaWorld? Should you?

================================================================

From: Tony Putman

Date: November 13, 2013 8:29:57 AM MST

A human is a Person with a Homo sapiens embodiment.

Persons have rights.

Proceed from there.

================================================================

From: Clarke Stone

Date: November 13, 2013 9:17:53 AM MST

Let's back off a bit and see if we can learn something. Following Tony's lead, let's imagine we are visited by creatures with non-homo-sap embodiment; that is, a flying saucer lands in Central Park, and critters descend the gangplank.

We take it that “someone” involved is a person, otherwise there wouldn't be a saucer. That kind of thing is indicative of social practices, civilization via division of labor (status), a lengthy ladder of significance, and so on. The object itself is evidence of a history of deliberate action.

But what about these critters coming down the gangplank? They might merely be the saucer-person's space-dogs, having got loose while the door was open. (Ain't it the way with dogs, even in space? Sheesh!) So...what are we looking for? What kinds of behaviors would give us reason to believe they were living out a history of social practices or deliberate action?

Let's try the reverse. What if the possibly space-dogs swarmed down the gangplank, jumped over and around one another, swirled around a bit, and went back up the gangplank? If we're trying to see them as persons, what is deliberate about that? What social practice could that be?

And at this point, we can look at "Planet of the Apes", the 1968 original. Taylor, the human protagonist, is merely shocked to see apes behaving like humans. But he takes them as persons very quickly and treats them as such very seriously. Why? He had only a few seconds to judge, he did judge, and the right way.

They, on the other hand, had never seen an instance of homo sap who was also a person, so they mistook him for what they'd seen before. Scriptwriter Rod Serling cleverly gave them reason to do so by cutting off Taylor's language ability via a throat injury, then let him plan to steal a notebook and write, showing he was a person. And not merely a very clever human imitating apes ("human see, human do"), but a creature who has significance to his actions. What was he doing by writing that? Proving he was a person.

So, is significance the thing we should be looking for in non-human behavior when looking for person-ish-ness? What are the dolphins doing by doing...what? How long is that ladder of significance? What is the extent of the social practices they do have? How much do social practices vary among groups of the same species?

================================================================

From: Joe Jeffrey

Date: November 13, 2013 12:46:59 PM MST

As Serling (and innumerable other people, including Pete) have recognized and somtimes said, language is crucial. It's crucial in a very specific way and for a very specific reason: once you move to non-human embodiments, the question of what you can recognize gets very hairy very fast. Consider CJ's possible-space-dogs. The very question has to be re-stated: What kinds of physical performances would give us reason to believe they were the performances of behaviors, rather than merely physical processes? And then, stipulating that we see, for example, processes that appear to be instances of acting on concepts not reducible to physical things (so that we're confident we're observing at least something more than mere physical processes), how could we determine that the maybe-behaviors comprise larger patterns -- social practices? Well, if we see them repeat. But that gets harder and harder to observe, the higher you go in the maybe-significance-ladder. I conjecture it gets exponentially harder each move up the possible-ladder. And the initial move, deciding it's not just physical movement, gets harder and harder the farther you get from non-human embodiment. It's not accidental that everybody in their right mind notices how person-like chimps, orangs, gorillas are, and it's almost that extreme with dogs. (I refuse to discuss the case of cats). And all that difficulty is because, as Pete once put it, "They can't tell us."

So I think caution is called for, on both sides. Calling whales slaves is brilliant rhetoric, but it's rhetoric, and not to be taken literally. Ya gotta be careful with that kind of thing (which is one of the important things Descriptive can bring to the table: the necessity for precision). If you're not, pretty soon you get extremists like PETA passing laws saying you can't call a dog a pet, only a companion animal, or killing human lab scientists to free the "enslaved" persons in the cages. On the other hand, seeing the complex sets of movements of whales, elephants, dolphins, etc., it's pretty damn hard to NOT say, "Geez, those sure look like behaviors." With all that implies: significance, community, and personhood.

Perhaps a practical maxim is in order: When you're dealing with a non-paradigm case, be careful.

================================================================

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 13, 2013 1:01:23 PM MST

Actually, I am concerned that we should err on the side of false positives rather than risk being wrong. Since there is considerable reason to see some Cetacea as language users, that potential is reason enough to be very careful regarding their use as chattel. The value of a Paradigm Case Formulation of persons is that it shows where agreement and disagreement occur. My concern is how to deal with ambiguity in the empirical findings. I think the ethical stance is to worry less about whether they aren't persons and more about whether they are. If they are, then we are enslaving them since slavery is a concept, like murder, that we apply to persons.

For many years the Australian government got away with not granting person status to some of its aboriginal people. Not exactly the same thing but they denied them that status initially on embodiment grounds.

================================================================

From: Tony Putman

Date: November 13, 2013 1:59:30 PM MST

There are two questions (at least) here:

Are whales (et. al) persons?

Should we grant rights to whales?

The first one is essentially an aesthetic question: do whales, as we know them, fit the paradigm case of person well enough to call them persons? The other is an ethical question: granted the current state of our knowledge about the person status of whales, should we grant them person rights? The answer to the first question lies somewhere between "Of course they fit!" and "Obviously they don't." Almost anyone today who is not merely debating the point will agree that it's a close call, even though some legitimately say "Yes" and others, "No."

So the ethical question becomes: In cases where the facts lead to both conclusions, but to neither conclusively, what is the ethically right thing to do? For this we can take guidance from well-established ethical standards, like "First, do no harm" to see that what we lose by granting rights that, as it turns out, were not warranted is greatly outweighed by what we lose by denying them when they turn out to have been warranted after all.

In short, the aesthetic question is a tough call; the ethical is not.

================================================================

From: Joe Jeffrey

Date: November 13, 2013 2:23:21 PM MST

I'm not addressing what side we should err on; I'm addressing the wisdom of slogans like calling whales slaves.

I'm very much in favor of erring on the side of "they're persons." But I'm not much in favor of firebrand slogans or extreme formulations of principles -- or extremist actions.

================================================================

From: Clarke Stone

Date: November 13, 2013 2:30:12 PM MST

I agree with Joe. It tends to polarize, and then the thinking stops. Tony's treatment is reasonable and gets at everyone's values.

================================================================

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 13, 2013 3:49:25 PM MST

It does.

================================================================

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 14, 2013 8:59:32 PM MST

In 2008, the Spanish Parliament mandated that the condition of slavery was illegal in property relations between humans and the other great primates: chimps, bonobos, orangs and gorillas. This was mandated as the State position to offer to the European Union. I think they found the concept of slavery precise rather than inflammatory. This last year the Indian government made the same point in regard the Cetacea.

I don't think we should be entertained by slaves of any sort or species. I also think the language of slavery is both polemical and politically precise.

================================================================

From: Clarke Stone

Date: November 15, 2013 5:58:38 AM MST

But not persuasive. I can't get people to bite down on the conversation if I'm bandying about a word like "slavery" when humans are starving, dying from lack of clean water, being sold into sex slavery, and so forth. It's an invitation to a dismissal.

================================================================

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 15, 2013 7:25:21 AM MST

And that's why it has a place in a political/legislative dialog specially targeted to jolt awareness (and that is also why it can go wrong). Many voices are always needed to find the language that fits and persuades in a political process.

================================================================

From: Greg Colvin

Date: November 15, 2013 8:16:30 AM MST

I'd say the best things we could do for the other species on the planet is not drive them to extinction, but it's too late for that.

As for "slavery" being inflammatory, I think it makes a difference that Europe abolished slavery three centuries before we did, and is not still suffering the wounds of a civil war about it. Even the claim that our civil war had to do with slavery can start an argument here.

And I think this is a difficult topic. Is my assistance dog a slave? I bought her, own her, and am responsible for her behavior. Is she a person? I think so. Do I have the right to keep her? At this point I feel obliged. We keep many animals for companionship, work, and food. Which of them are persons? And when they are, do we have the right to keep them, let alone eat them?

I think the issue is usually not whether we have a right to keep animals, but whether we treat them humanely. Which was the issue for slaves for thousands of years. The US not only held slaves for hundreds of years after Europe, but refused to recognize slaves as persons, or even treat them humanely.

So what about whales, dolphins, elephants, horses, dogs, cats...? What about apes, bears, wolves, coyotes, lions...? What about oaks, pines, and roses? With persons as the paradigm case, they are all describable as persons, but some more than others. (Animal Farm?)

So is the issue with Cetacea that they are persons? Or that we are not able to keep them humanely?

Anyway, these are lovely videos about dogs and elephants who are best friends:

================================================================

From: Tony Putman

Date: November 15, 2013 10:24:11 AM MST

Nice, Greg.

================================================================

From: Clarke Stone

Date: November 15, 2013 12:59:51 PM MST

It's taken me a little while to figure out what bothers me about invoking slavery on the Cetacean issue, but here it is: it's a degradation. You are saying to other people, "This is an ethical matter that everyone should see the same way ("slavery is bad"), so if you don't, there's something wrong with you--you're unethical." Degradation elicits self-affirmation, so you can't get agreement ("You're right, I'm morally defective"), only statements like "Now hold on. I'm <a good person>, not <a bad person>"; and "Who are you to tell me X about Y?" questioning your status to make any such judgment, period, let alone about any particular individual.

In common terms, it's a personal attack.

This move flips the argument from the ethical perspective to the aesthetic perspective (as described by Tony), that is, into a realm where there is no resolution.

Degradation and "permanent argument"--can't see the advantages, esp. given that the Cetaceans have a clock ticking against them.

Can someone suggest an approach that accredits, clarifies, and unifies? or implements Tony's analysis?

================================================================

From: Greg Colvin

Date: November 15, 2013 1:29:07 PM MST

Of course, it depends. What flies in Spanish politics doesn't fly in America. What offends one friend or family member doesn't bother another. And so on. But Descriptive tools can at least do justice to the complexity of the question.

So more complexities: for some species, and more to come, zoos and other captive situations are the only hope of survival. Is it then ethical to keep them? And is it then ethical to play games with them? And is it ethical to have others pay to watch the games, so as to fund their upkeep? And are these games the animal is being coerced to play? And if they are coerced, is that unethical? After all, in our culture we commonly make our children do things they don't want to. And force adults to work on pain of hunger, exposure, and death. We used to force children to work, too.

My personal experience is that as a boy I got to swim with a captive porpoise named Mitzi, who played Flipper on TV. She surfaced alongside me and let me hold her fin as she pulled me. For me it was magical. For her? I don't know whether she considered herself a degraded slave, or an honored ambassador.

================================================================

From: Wynn Schwartz

Date: November 15, 2013 2:07:03 PM MST

Yes, you don't know and she couldn't tell you. People are always only as free as the boundaries of their cells but in the case of Mitzi she was forced into one of ours. When Kunta Kente ended up in South Carolina, did he eventually find friendship? Maybe. That coercion and degradation limit the available options is the political/power theme that interests me. There are, of course, other considerations.

And whatever is limiting the survival of the Great Apes and some of the Cetacea, it is mostly on us and not them.

================================================================

From: Greg Colvin

Date: November 15, 2013 3:43:42 PM MST

Yes, even without abusing species in captivity we are driving them to extinction.

I did some Googling on Mitzi. She starred in the 1963 and 1964 movies, but not the TV series. I found a picture of a woman swimming with her in the same place I did. You can imagine the impact on a ten year old. It would probably be better for her had she never been captured, but indeed I couldn't ask her.

I'd say for many animals that we have learned enough from our captives to know that they probably should not be captives. There are alternatives:

================================================================

From: Greg Colvin

Date: November 15, 2013 3:50:15 PM MST

-- Bob Marley

(Hyperlinks connect some of the relevant terms to specific resources. Other resources can be found on the Descriptive Psychology Facebook site.)

Some of the discussion above involved the Descriptive Psychology community's use of a method, Paradigm Case Formulation, and a specific conceptualization of "Persons".

A Person is a Cognizant individual whose actions are, paradigmatically, Deliberate Actions, i.e., actions in which a person knows what he is doing and chooses to do it. Patterns of deliberate action follow from the actor's hedonic, prudent, aesthetic and ethical reasons for doing one thing or another. Verbal Behavior, as an expression of linguistic competence, is a form of Deliberate Action paradigmatic of Persons.

Further, Deliberate Actions are also Social Practices selected and attempted by what a person finds Significant. Patterns of social practices with their results create intelligible "Through-Lines" that are elements in the "Dramaturgical Pattern" of a Person's life.

One use of a Paradigm Case Formulation is to facilitate clarity about agreement and disagreement regarding whether something counts as a proper example of a case in question. Another is to identify cases where some but not all aspects apply and to treat and respect those cases accordingly. A competent judge could argue that even without all of the elements of the paradigm case present, it is still appropriate to treat an entity as a Person. Different judges might have different criteria for what is sufficient but a paradigm case formulation should allow them to know where they agree or disagree.

A troubling and significant ethical question remains: After the line on personhood is drawn, what considerations apply to the treatment of animals that do not fall into the person category? Since all sentient animals have an interest in the avoidance of suffering, when is it ethical to inflict harm on any animal?

Person status defines a domain where social and legal rights reside, hence a proper abhorrence with slavery. Judges in good faith may differ as to what animals are included as persons, but it is a moral and ethical mistake to limit concerns with the quality of life to whether that animal is also a person.

Postscript June 3, 2016

|

| Harambe RIP |

The major problem is that the Cincinnati Zoo is legally permitted to treat such extraordinarily cognitively complex and gentle animals as slaves […] and that Harambe, like every other nonhuman animal, was a legal 'thing' that lacked the capacity for any legal rights, even the fundamental rights to his life and liberty.

Steven Wise